|

|

||

|

Other languages: Deutsch

| Esperanto

| Français | עברית

| Italiano | Nederlands | Polski | Português | Simple

English | Svenska |

||

www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda#Nazi_Germany

Propaganda

From

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Propaganda is a specific type of message

presentation, aimed at serving an agenda. Even if the message conveys true

information, it may be partisan and fail to paint a complete picture. The

primary use of the term is in political contexts. A similar manipulation of

information is well known, e.g., in advertising,

but normally it is not called propaganda in the latter context.

North Korean

propaganda showing a soldier destroying the US Capitol

|

Table of

contents [hide] |

|

1

History of the word propaganda 3.1 Nazi Germany 4

Techniques of propaganda generation |

History of the word propaganda

In late Latin, propaganda

meant "things to be propagated". In 1622, shortly after the

start of the Thirty Years' War, Pope

Gregory XV founded the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide

("congregation for propagating the faith"), a committee of Cardinals to oversee the propagation of Christianity

by missionaries

sent to non-Christian countries. Originally the term was not intended to refer

to misleading information. The modern political sense dates from World War I,

and was not originally pejorative.

Kinds

of propaganda

Propaganda shares many techniques

with advertising;

in fact, advertising can be said to be propaganda promoting a commercial

product. However, propaganda usually has political or nationalist

themes. It can take the form of leaflets, posters, TV broadcasts or radio broadcasts.

In a narrower and more common use

of the term, propaganda refers to deliberately false or misleading information

that supports a political cause or the interests of those in power. The

propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation,

for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are

desirable to the interest group. In this sense, propaganda serves as a

corollary to censorship, in which the same purpose is achieved, not by

filling people's heads with false information, but by preventing people from

knowing true information. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of

advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's

understanding through deception and confusion, rather than persuasion and

understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one

sided or untrue but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help

to disseminate the propaganda.

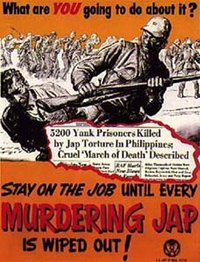

Anti-Japanese propaganda from the

United States from World War II

Propaganda is a

mighty weapon in war.

In this case its aim is usually to dehumanize the enemy and to create hatred

against a supposed enemy, either internal or external. The technique is to

create a false image in the mind. This can be done by using special words,

special avoidance of words or by saying that the enemy is responsible for

certain things he never did. Most propaganda wars require the home population

to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be

based on facts. The home population must also decide that the cause of their

nation is just.

Propaganda is also one of the

methods used in psychological warfare. More in line with the

religious roots of the term, anti-cult activists accuse the leaders of cults of using

propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them.

Examples of political

propaganda:

- British

propaganda against Germany in the First

World War, see RMS Lusitania

- German

propaganda against Poland to start the Second World War, see Attack on Sender Gleiwitz

In an even narrower, less

commonly used but legitimate sense of the term, propaganda refers only to false

information meant to reassure people who already believe. The assumption is

that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by

doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant (see cognitive dissonance), people will be eager to

have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of

those in power. For this reason propaganda is often addressed to people who are

already sympathetic to the agenda.

Propaganda can be classified

according to the source. White propaganda comes from an openly

identified source. Black propaganda pretends to be from a

friendly source, but is actually from an adversary. Gray propaganda

pretends to be from a neutral source, but comes from an adversary.

Propaganda may be administered in

very insidious ways. For instance, disparaging disinformation

on foreign countries may be tolerated in the educational system. Since few

people actually double-check what they learn at school, such disinformation

will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea

that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even

though no one repeating the myth is able to point to a definite authoritative

source or facts. The desinformation is then recycled in the media and in the

educational system. For instance, in English-speaking countries such as the United

Kingdom and the United States, many people are persuaded that

countries such as France

don't have presumption of innocence because they

apply the "Napoleonic Code", ignoring the fact that the

laws concerning criminal procedures have been rewritten several times since

Napoleon's days and that even in Napoleon's days, there was no legal

presumption of guilt (only little rights for the defense compared to nowadays'

standards).

Such permeating propaganda may be

used for political goals: by giving to citizens a false impression of the

quality or uniqueness of their country, they may be incited to reject certain

proposals or certain remarks, or ignore the experience of others.

See also: black

propaganda, marketing, advertising

History of propaganda

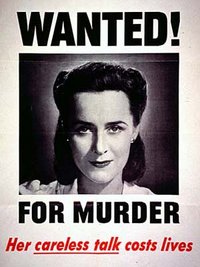

U.S. propaganda poster (National

Archives)

Propaganda has

been a human activity as far back as reliable recorded evidence exists. The

writings of Romans like Livy

are considered masterpieces of pro-Roman statist propaganda. The term itself

originates with the Roman Catholic Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of

the Faith (sacra congregatio christiano nomini propagando or, briefly,

propaganda fide), the department of the pontifical administration charged

with the spread of Catholicism and with the regulation of ecclesiastical

affairs in non-Catholic countries (mission territory). The actual Latin stem propagand-

conveys a sense of "that which ought to be spread".

Propaganda techniques were first

codified and applied in a scientific manner by journalist Walter

Lippman and psychologist Edward

Bernays (nephew of Sigmund Freud) early in the 20th

century. During World War I, Lippman and Bernays were hired by the United

States President, Woodrow Wilson to participate in the Creel Commission,

the mission of which was to sway popular opinion to enter the war on the side

of Britain.

The war propaganda campaign of

Lippman and Bernays produced within six months so intense an anti-German

hysteria as to permanently impress American business (and Adolf

Hitler, among others) with the potential of large-scale propaganda to

control public opinion. Bernays coined the terms "group mind" and

"engineering consent", important concepts in practical propaganda

work.

The current public

relations industry is a direct outgrowth of Lippman and Bernays' work and

is still used extensively by the United States government. For the first half

of the 20th century Bernays and Lippman themselves ran a very successful public

relations firm.

World War

II saw continued use of propaganda as a weapon of war, both by Hitler's

propagandist Joseph Goebbels and the British Political

Warfare Executive.

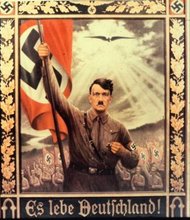

Nazi

Germany

Nazi poster subtly comparing

Hitler to Jesus Christ. Text: "Long Live Germany!"

Most propaganda in Germany was

produced by the Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda

("Promi" in German abbreviation). Joseph

Goebbels was placed in charge of this ministry shortly after Hitler took

power in 1933. All

journalists, writers, and artists were required to register with one of the

Ministry's subordinate chambers for the press, fine arts, music, theater, film,

literature, or radio.

The Nazis believed in propaganda

as a vital tool in achieving their goals. Adolf

Hitler, Germany's Führer, was impressed by the power of Allied propaganda during

World

War I and believed that it had been a primary cause of the collapse of

morale and revolts in the German home front and Navy in 1918 (see also: November criminals). Hitler would meet nearly

every day with Goebbels to discuss the news and Goebbels would obtain Hitler's

thoughts on the subject; Goebbels would then meet with senior Ministry

officials and pass down the official Party line on world events. Broadcasters

and journalists required prior approval before their works were disseminated.

In addition Adolf Hitler and some other powerful high ranking

Nazis like Reinhard Heydrich had no moral qualms about

spreading propaganda which they themselves knew to be false, and indeed

spreading deliberately false information was part of a doctrine known as the Big Lie.

Nazi propaganda before the start

of World War II had several distinct audiences:

- German audiences were continually reminded of

the struggle of the Nazi Party and Germany against foreign enemies and

internal enemies, especially Jews.

- Ethnic Germans in countries such as Czechoslovakia,

Poland, the

Soviet

Union, and the Baltic states were told that blood ties to

Germany were stronger than their allegiance to their new countries.

- Potential enemies, such as France and Britain,

were told that Germany had no quarrel with the people of the country, but

that their governments were trying to start a war with Germany.

- All audiences were reminded of the greatness

of German cultural, scientific, and military achievements.

Until the Battle of Stalingrad's conclusion on February 4,

1943, German

propaganda emphasized the prowess of German arms and the humanity German

soldiers had shown to the peoples of occupied territories. In contrast, British

and Allied fliers were depicted as cowardly murderers, and Americans in

particular as gangsters in the style of Al Capone.

At the same time, German propaganda sought to alienate Americans and British

from each other, and both these Western belligerents from the Soviets.

After Stalingrad, the main theme

changed to Germany as the sole defender of Western European culture against the

"Bolshevist hordes." The introduction of the V-1 and V-2 "vengeance

weapons" was emphasized to convince Britons of the hopelessness of

defeating Germany.

Goebbels committed suicide shortly

after Hitler on April

30, 1945. In his

stead, Hans Fritzsche, who had been head of the Radio

Chamber, was tried and acquitted by the Nuremberg

war crimes tribunal.

Cold

War propaganda

The United States and the Soviet

Union both used propaganda extensively during the Cold War.

Both sides used film, television and radio programming to influence their own

citizens, each other and Third World nations. The United States Information Agency

operated the Voice of America as an official government

station. Radio Free Europe and Radio

Liberty, in part supported by the Central Intelligence Agency, provided

grey propaganda in news and entertainment programs to Eastern Europe and the

Soviet Union respectively. The Soviet Union's official government station,

Radio Moscow, broadcast white propaganda, while Radio Peace and Freedom

broadcast grey propaganda. Both sides also broadcast black propaganda programs

in periods of special crises.

The ideological

and border dispute between the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China resulted in a

number of cross-border operations. One technique developed during this period

was the "backwards transmission," in which the radio program was

recorded and played backwards over the air.

In the Americas, Cuba served as a

major source and a target of propaganda from both black and white stations

operated by the CIA and Cuban exile groups. Radio Habana Cuba, in turn,

broadcast original programming, relayed Radio Moscow, and broadcast The

Voice of Vietnam as well as alleged confessions from the crew of the USS Pueblo.

One of the most insightful

authors of the Cold War was George Orwell, whose novels Animal Farm

and Nineteen Eighty-Four are virtual

textbooks on the use of propaganda. Though not set in the Soviet Union, their

characters live under totalitarian regimes in which language is constantly

corrupted for political purposes. Those novels were used for explicit

propaganda. The CIA,

for example, secretly commissioned an animated

film adaptation of Animal Farm in the 1950s.

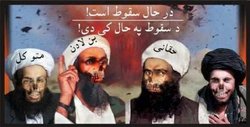

Afghanistan

PsyOps leaflet dropped in

Afghanistan. Text: "The Taliban's reign of fear is about to end."

In the 2001

invasion of Afghanistan, psychological operations tactics (PsyOps)

were employed to demoralize the Taliban and to win the sympathies of the Afghan population.

At least six EC-130E

Commando Solo aircraft were used to jam local radio transmissions and

transmit replacement propaganda messages.

Leaflets were also dropped

throughout Afghanistan, offering rewards for Usama

bin Laden and other individuals, portraying Americans as friends of

Afghanistan and emphasizing various negative aspects of the Taliban. Another

shows a picture of Mohammed Omar in a set of crosshairs with the words

“We are watching”, presumably to convince individuals and groups that resistance is futile.

Techniques of propaganda generation

![]()

Saddam

Hussein pictured as a decisive war leader in an Iraqi propaganda picture

A number of

techniques are used to create messages which are persuasive, but false. Many of

these same techniques can be found under logical

fallacies since propagandists use arguments which, although sometimes

convincing, are not necessarily valid.

Some time has been spent

analyzing the means by which propaganda messages are transmitted, and that work

is important, but it's clear that information dissemination strategies only

become propaganda strategies when coupled with propagandistic messages.

Identifying these propaganda messages is a necessary prerequisite to studying

the methods by which those messages are spread. That's why it is essential to

have some knowledge of the following techniques for generating propaganda:

Appeal

to fear: Appeals

to fear seek to build support by instilling fear in the general population -

for example Joseph Goebbels exploited Theodore Kaufman's

Germany Must Perish!

to claim that the Allies sought the extermination of the German people.

Appeal to authority: Appeals to authority cite prominent

figures to support a position idea, argument, or course of action.

Bandwagon: Bandwagon-and-inevitable-victory appeals

attempt to persuade the target audience to take a course of action

"everyone else is taking." "Join the crowd." This technique

reinforces people's natural desire to be on the winning side. This technique is

used to convince the audience that a program is an expression of an

irresistible mass movement and that it is in their interest to join.

"Inevitable victory" invites those not already on the bandwagon to

join those already on the road to certain victory. Those already, or partially,

on the bandwagon are reassured that staying aboard is the best course of

action.

Obtain disapproval: This technique is used to get the

audience to disapprove an action or idea by suggesting the idea is popular with

groups hated, feared, or held in contempt by the target audience. Thus, if a

group which supports a policy is led to believe that undesirable, subversive,

or contemptible people also support it, the members of the group might decide

to change their position.

Glittering generalities: Glittering generalities are intensely emotionally

appealing words so closely associated with highly valued concepts and beliefs

that they carry conviction without supporting information or reason. They

appeal to such emotions as love of country, home; desire for peace, freedom,

glory, honor, etc. They ask for approval without examination of the reason.

Though the words and phrases are vague and suggest different things to

different people, their connotation is always favorable: "The concepts and

programs of the propagandist are always good, desirable, virtuous."

Rationalization: Individuals or groups may use favorable

generalities to rationalize questionable acts or beliefs. Vague and pleasant

phrases are often used to justify such actions or beliefs.

Intentional vagueness: Generalities are deliberately vague so

that the audience may supply its own interpretations. The intention is to move

the audience by use of undefined phrases, without analyzing their validity or

attempting to determine their reasonableness or application

Transfer: This is a technique of projecting

positive or negative qualities (praise or blame) of a person, entity, object,

or value (an individual, group, organization, nation, patriotism, etc.) to

another in order to make the second more acceptable or to discredit it. This

technique is generally used to transfer blame from one member of a conflict to

another. It evokes an emotional response which stimulates the target to

identify with recognized authorities.

Oversimplification: Favorable generalities are used to

provide simple answers to complex social, political, economic, or military

problems.

Common man: The "plain folks" or

"common man" approach attempts to convince the audience that the

propagandist's positions reflect the common sense of the people. It is designed

to win the confidence of the audience by communicating in the common manner and

style of the audience. Propagandists use ordinary language and mannerisms (and

clothes in face-to-face and audiovisual communications) in attempting to

identify their point of view with that of the average person.

Testimonial: Testimonials are quotations, in or out

of context, especially cited to support or reject a given policy, action,

program, or personality. The reputation or the role (expert, respected public

figure, etc.) of the individual giving the statement is exploited. The

testimonial places the official sanction of a respected person or authority on

a propaganda message. This is done in an effort to cause the target audience to

identify itself with the authority or to accept the authority's opinions and

beliefs as its own. See also, damaging quotation

Stereotyping or Labeling: This technique attempts to

arouse prejudices in an audience by labeling the object of the propaganda

campaign as something the target audience fears, hates, loathes, or finds

undesirable. For instance, reporting on a foreign country or social group may

focus on the stereotypical traits that the reader expects, even though they are

far from being representative of the whole country or group; such reporting

often focuses on the anecdotal.

Scapegoating: Assigning blame to an individual or

group that isn't really responsible, thus alleviating feelings of guilt from

responsible parties and/or distracting attention from the need to fix the

problem for which blame is being assigned.

Virtue

words: These are

words in the value system of the target audience which tend to produce a

positive image when attached to a person or issue. Peace, happiness, security,

wise leadership, freedom, etc., are virtue words.

Slogans: A slogan is a brief striking phrase that

may include labeling and stereotyping. If ideas can be sloganized, they should

be, as good slogans are self-perpetuating memes.

See also doublespeak,

brainwashing,

mind

control, information warfare, meme, psyops

Techniques of propaganda transmission

Common methods for transmitting

propaganda messages include news reports, government reports, historical

revision, junk science, books, leaflets, movies,

radio , television

, and posters. In the case of radio and television, propaganda can exist on

news, current-affairs or talk-show segments, as advertising or public-service

announce "spots" or as long-running advertorials.

See Also

- Public diplomacy, the term used by the USIA to describe

its mission

- News

management, more subtle techniques for influencing the public

perception of organizations/governments via the news media.

- List of

topics related to public relations and propaganda

- Tanaka

Memorial

References

- Disinfopedia,

the encyclopedia of propaganda

- Howe, Ellic. The Black Game: British

Subversive Operations Against the German During the Second World War.

London: Futura, 1982.

- Edwards, John Carver. Berlin Calling:

American Broadcasters in Service to the Third Reich. New York, Prager

Publishers, 1991.

ISBN

0-275-93705-7.

- Linebarger, Paul M. A. (aka Cordwainer Smith). Psychological Warfare.

Washington, D.C., Infantry Journal Press, 1948.

- Shirer, William L. Berlin Diary: The

Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1934-1941. New York: Albert A.

Knopf, 1942.

- Much of the information found in Propaganda

techniques is take from: "Appendix I: PSYOP Techniques" from

"Psychological Operations Field Manual No.33-1" published by

Headquarters; Department of the Army, in Washington DC, on 31 August 1979. (partial contents here)

- The [PsyWarrior]

- New Scientist: [Psychological

warfare waged in Afghanistan]

See also: propaganda

film, propaganda model, Logical

fallacy, political media, ideology, spin,

public

relations, marketing, Information warfare, CNN, BBC, agitprop, political campaigning.

External

links

- propaganda critic: A website

devoted to propaganda analysis.

- David

Welch: Powers of Persuasion

- Documentation on

Early Cold War U.S. Propaganda Activities in the Middle East by the

National Security Archive. Collection of 148 documents and overview essay.

- Bibliography

on the British Political Warfare Executive

- Propaganda

techniques list from Disinfopedia

- Propaganda

defined more technically, also from Disinfopedia

- Sacred Congregation of

Propaganda from the Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Propaganda: The Formation of

Men's Attitudes by Jacques Ellul--excerpts

- Stefan Landsberger's Chinese

Propaganda Poster Pages

- Propaganda Communist Chinese Paintings

(site in french)

- Bytwerk, Randall, "Nazi and East

German Propaganda Guide Page". CAS Department, Calvin

College.

- [Nazi Posters:

1933-1945]

Propaganda were a 1980s UK pop group signed to Paul Morley

and Trevor

Horn's ZTT record

label.

Propaganda is also a compilation

album released in the United Kingdom which contains songs by various

artists, including The Police and Joe Jackson